- Home

- Juliet Barnes

The Ghosts of Happy Valley Page 2

The Ghosts of Happy Valley Read online

Page 2

During the trial, Alice, Idina and Phyllis dressed up in their best and sat together, glaring at Diana’s beautifully clad back. No doubt plenty of other women in court fantasised about hurling invisible poisoned arrows at her too. If any of them knew anything about the murder, they never let on. Or had they simply all been too drunk that fateful night to remember what had happened?

Nothing was concluded and nobody was found guilty, but ever since there has been much speculation as to Erroll’s killer and the motive, and endless research has gone into seeking the truth. The Happy Valley hype has also kept the stories alive: far more than if the victim had been just a hard-working, happily married settler.

Sir Jock killed himself the following year. Diana Broughton, meanwhile, grieved for two years before marrying the reclusive and rich landowner, Gilbert Colville. She even persuaded him to buy her the home where her late lover had lived with his wife Mary. In 1955, fourteen years after the murder, Diana married a fourth time; this time the man she chose was Lord Delamere, Colville’s best friend and neighbour.

Almost a century later, that irresistible intrigue still lingers on from the heyday of Kenya’s infamous Happy Valley, two giddy decades that climaxed in the unresolved murder of Lord Erroll. Controversy remains, although many authors have come up with theories since the first whodunnit book, James Fox’s White Mischief (1982) – made into a major feature film starring Charles Dance, Greta Scacchi and Joss Ackland – reignited interest in the case. The man (some say woman) who fired a bullet into the brain of the philandering earl died with his (or her) secret. Surprisingly, perhaps, none of the other members of the hedonistic Happy Valley inner circle ever kissed and told either.

Solomon was a small boy when Kenya became independent from British rule in 1963: white settlers were leaving and their farms were being divided up and allocated to native Kenyans. As the years passed, he watched the rapid population growth of his own Kikuyu people as they spurred on mindless destruction of the indigenous mountain forests. Today the continued demise of the trees causes formerly reliable rivers to alternately dry up and flood, washing down valuable topsoil into the lakes of the Rift Valley. Solomon’s book has no happy endings.

After exchanging pleasantries with the other guests, I asked Solomon about his conservation work, carried out on an entirely voluntary basis. He talked without restraint, his husky voice rising and falling musically, fraught with conviction and emotion. His poor English surprised me – I’d expected this man, who very clearly intends to change things, to be more sophisticated. Rural Kenyan subsistence farmers tend to have more immediately pressing problems than saving trees or wild animals, which respectively represent bags of charcoal and pests. Like the majority of Kenya’s rapidly growing rural population, Solomon has always lived in a simple homestead with no electricity or running water; there are few maintained access roads or other communications, and the inhabitants’ educational opportunities are limited.

He gesticulated with thin, sensitive hands, smiling broadly as he talked passionately about monkeys and trees, but frowning suddenly when he mentioned the mounting threats to both. There was something dynamic about Solomon: his enthusiasm, winning smile and positive attitude were infectious.

We paused to listen to the sing-song bray of the zebra. A bachelor herd of impala were jumping through the thorn bush, kicking up the dust into a cloudless, blue sky. I asked Solomon about his ‘book’, whose story he had introduced with an unexpected comparison:

If you don’t know Happy Valley, try to visit the area. All around Happy Valley are many historic houses. The spirits of the dead white people who used to live in these houses are living on in the African people who live there now . . . As I read the book White Mischief I saw that there is no big difference between these white people and the modern African living in Happy Valley.

The air was dry and I could smell something dead – the hyenas and jackals would be out tonight. Apart from the indomitable scarlet bougainvillaea bushes, my garden was like a desert. I thought about how unlikely it seemed for a black Kenyan to display any interest in a set of colonial characters who appeared to have attracted posthumous fame by doing nothing constructive, yet our conversation over cups of tea and scones with Cape gooseberry jam (made by one of the artists) soon switched from Solomon’s book to the old houses in Happy Valley.

Today’s significant landowners in Happy Valley are vastly wealthy black politicians, in spite of constant low mutterings about the source of their gains. In the former farming lands dubbed the ‘white highlands’ – which surround and include Happy Valley – it’s not uncommon to find a farm owned by a powerful politician, an absentee landlord with numerous other business interests. While his wife flies to Europe to buy designer clothes and his children are privately educated in Britain or America, his farm workers are seldom paid much above the minimum wage for unskilled labour, living on less in a month than their boss will spend on a bottle of imported Champagne at Muthaiga Club.

The passenger train, ‘the lunatic line’, originally built by the British at vast expense, no longer runs daily from Mombasa to Nairobi, nor on to Kisumu. The tiny station at Gilgil in the Rift Valley was once the stepping-off point for white passengers headed for Happy Valley and beyond, who usually paused at the Gilgil Hotel, opened in 1920 by Lady Colville, mother of Gilbert and briefly mother-in-law to Diana. Today few passengers disembark at Gilgil and none of them are white. The Gilgil Hotel, having changed ownership several times, after Kenya’s independence became a brothel, is scathingly referred to as the ‘Moulin Rouge’ by Gilgil’s white community. Today it provides squalid dwellings for many families in an expanding, increasingly scruffy roadside town which became flooded with internally displaced Kenyans during the post-election violence at the beginning of 2008. Up the various roads from Gilgil to Happy Valley, the land remains predominantly in Kikuyu hands. The population grows steadily, the farms become smaller, creating an intricate patchwork landscape, their edges blurred by non-indigenous fast-growing trees. The forest recedes, and the Aberdares and Kipipiri regularly burn.

‘I can take you to the Happy Valley,’ said Solomon, helping himself to another scone. ‘You can write the story!’

I’d always wanted to explore the area: I’d read White Mischief, which told of a house called Clouds that had been the headquarters for wild sessions of carousing before you traded in your husband for a night with somebody else’s. I was dubious about unearthing yet another who-killed-the-Earl-of-Erroll theory, let alone replaying what went on at those parties thrown by Lady Idina. But the prospect of seeing Happy Valley’s old, abandoned homes was interesting. So was the idea of getting to know Solomon and finding out what had inspired him to follow so single-mindedly such an unusual bent. As Ralph Waldo Emerson once said, ‘The use of history is to give value to the present hour and its duty.’ But I’d add Goethe’s view, that the ‘best thing which we derive from history is the enthusiasm that it raises in us’.

Clouds was still standing, people said. Somebody had seen it from the air, but nobody knew how to get there by road.

‘You won’t see a white face there nowadays,’ an elderly, retired white farmer had warned.

‘All those roads are appalling!’ another had cautioned.

‘In this day and age, you’ll get mugged in that area – it’s all Kikuyu country now!’ the farmer had continued. ‘You mustn’t go alone.’

‘You ought to find somebody who has a gun to accompany you,’ an even more twitchy old-timer had said to me.

Solomon certainly doesn’t have a gun – I can’t imagine him killing a cockroach. But his wanderings through the area on foot have familiarised him with the whereabouts of all the decaying ruins, once people’s homes. And his native language is Kikuyu, making him the perfect guide.

‘When you see these old houses of white people,’ Solomon said conspiratorially, ‘then you will want to write the true histories!’

I was less sure. At this point he was ju

st a potential guide into an area which had always had some mysterious allure for me.

‘There are some stories,’ continued Solomon, widening his eyes. ‘Terrible stories. You will be the first white person to hear.’

‘You can write about the old houses,’ suggested one of the artists, adding a few touches to her picture of flamingos.

A sudden gust of dry wind blew clouds of dust on to the veranda and we covered our teacups with our hands.

2

Destination Unknown

Early one February morning in 2000, I met Solomon at an uninspiring roadside village called Captain, a bumpy hour’s drive from my home. ‘After Captain Colville,’ said Solomon. According to Gilgil old-timer Ray Terry, this was Captain Archie Colville, no relation to the Colville who became the third husband of Diana Broughton. Captain, the village, sprawls untidily along a junction off the main road from Gilgil to Nyahururu. The latter was formerly called Thomson’s Falls after Scottish explorer Joseph Thomson first admired the waterfall in 1883.

Leaving the tarmac, we made a right-hand turn and headed towards the distant blue hulk of the Aberdares, the flow of conversation stifled by the protesting rattles of my old Land Rover as it jostled along the rocky, rutted road, marked on the map as the ‘old Wanjohi road’. Solomon, shouting above the noise of the car, pointed out old settlers’ homes, barely recognisable as such in this heavily populated country. Today’s newer Kikuyu homesteads were an incongruous mix of one-roomed houses on small plots and larger farms – weekend pads flaunting large, tiled red roofs. Many of the latter homes were owned by wealthy politicians, whom Solomon named with a disapproving air. At that time no white people lived in Happy Valley except for one Dutchman growing flowers for a wealthy Kenyan. The occasional voluntary worker passed through, Solomon said, but in some villages we visited, the children I met had never seen a white person.

As we slowly drew closer to the blue hulk of the Aberdares, I felt a prickle of excitement and wondered if I had a pen and notebook anywhere in the car. I hadn’t even taken a camera. This spontaneous Happy Valley tour was just supposed to be an interesting day out.

So it was to prove. I hauled my Land Rover over miles more of rocky, potholed roads, deep channels and gullies gouged out of their neglected surfaces by the previous years’ long rains, which had included the torrential downpours and subsequent floods of 1997’s El Niño. We stopped to look at some old tumbledown homes, hidden behind untrimmed cypress hedges 30-feet high, cedar fence posts covered in wisps of green ‘old man’s beard’, remains of stores, cattle dips and bridges that Solomon said had been built in the 1920s. I paused to marvel at an old rose scrambling over a piece of wall: a reminder of some faceless, pale, foreign lady who would have ordered its planting. Undeterred by fifty-plus subsequent years of neglect, the bush had somehow survived, even without that meagrely paid ‘garden boy’ to tend it.

Some houses were completely intact. Others had vanished, leaving only a foundation stone or brick chimney. Some of these once-luxurious dwellings lay empty – allegedly haunted. Rooms of others were now homes for many local families, or poorly funded schools. Most of these people were extremely poor by any standards, and yet they offered us unconditional hospitality – we were invited in for tea, even expected to share their meal. An underpaid government schoolteacher said he was writing the history of the Mau Mau uprising in that area – could I publish it? Another white-haired, half-blind man to whom we gave a lift chuckled when he told us he remembered ‘those white people’ . . .

Our final destination near the end of that long, exhausting day was planned to be Clouds itself, which according to popular rumour had been the whirlpool of Happy Valley, the place where you got sucked in: the sexy and seductive Lady Idina had lived here and unashamedly thrown those decadent parties which supposedly titillated her guests to plunge into erotic adventures. ‘Are you married or do you live in Kenya?’ has always been considered a great joke, well tossed among the G&Ts and Scotch. Happy Valley has permanently been painted into Kenya’s history, albeit with a British brush. The fascination lingers, fanned by its frequently rewritten legend.

The Anglo-German agreement of 1890 partitioned East Africa into British and German zones and the interior of Kenya became a British protectorate in 1895. Kenya’s best farming land lies in the highlands, covering less than 25 per cent of a predominantly semi-arid country. The prime land with well-watered, fertile soil and two annual rainy seasons included what would later be named ‘Happy Valley’ – the area around the Wanjohi Valley and Kipipiri – invitingly unpopulated at that time, with only the occasional Dorobo honey hunter passing through the lush forests and green glades. It was also a route between grazing grounds for the nomadic Maasai, whose stamp was left in the names of certain features – Kipipiri is Maasai.

The first white settler in this area was Geoffrey Buxton, who arrived in 1906, building his mud and brick house a few years later: Happy Valley’s first English-style house. The Soldier Settlement Scheme of 1919 saw further allocation of land in British East Africa, with 99- and 999-year leases being offered to settlers of pure European origin who had served in an officially recognised imperial service unit. This was an attempt to increase the white population, while bringing economic development to the area. But it was also about protection: there was the new threat of African unrest after African troops who’d fought in the First World War had seen how easily white men could be killed.

The scheme attracted plenty of old Etonians. The war had interrupted the careers of a whole generation, but their settlement in Africa eased their passage to peace and gave them the added attraction of retaining their status among uneducated Africans. Kenya, proclaimed a colony in 1920, was already acquiring a reputation as ‘the Officers’ Mess’. The Africans, meanwhile, now had taxes thrust upon them by Britain, coercing them to take paid work as labourers in Nairobi or on white farms. Nor were they allowed to grow crops for export in case they lowered the standards.

There followed the fleeting era of Lady Idina and her like-minded pleasure-seeking friends, their indulgent lifestyle swept away by the Second World War. Afterwards things changed fast. There was a further influx of white settlers escaping Britain’s post-war austerity, high taxes and the Labour government. By the beginning of the 1950s the old Happy Valley crowd had faded away: most of the larger estates had been divided up into smaller farms, albeit still large by British standards. The houses where earlier settlers had partied with reckless abandon were now homes for different sorts of families. On the whole these white settlers were not aristocratic or affluent and were working hard to make a living out of sheep and pyrethrum – the latter a cash crop that grows well in Kenya’s highlands and whose flowers are used in the manufacture of insecticides. Now settler wives tended to be too busy teaching their own children, market gardening, tending English flowers and making jams and pickles, to parade around in designer gear casting lascivious glances at neighbours’ husbands. But their lifestyle wasn’t destined to last any longer than that of their predecessors.

Back in 1907 Winston Churchill had warned, after visiting Kenya, ‘There are already in miniature all the elements of keen racial and political discord.’ Almost half a century later no black man even had the right to vote, let alone claim his sacred, ancestral land. The banned underground resistance movement that had begun in the 1940s as the Kikuyu Central Organisation was by the early 1950s showing strong aversion to British rule, its members taking oaths in secret to pledge solidarity. In 1952 a state of emergency was declared. The eight-year Mau Mau uprising was a threat to the existence of white farmers and Happy Valley was right in the thick of it.

Settlers now lived in terror of their formerly loyal staff turning against them and collaborating in their murder. Cows were hamstrung; Kikuyu people were disembowelled and hacked to pieces if they did not pledge loyalty to Mau Mau. Several white farmers were viciously attacked: on the Kinangop, not far from Clouds, the Rucks and their young son were butchered,

the child in his bed. Then there was the grisly murder of two white farmers, Charles Fergusson and Richard Bingley, as they sat down to dinner in their home on the northern edge of Happy Valley. As Kikuyu freedom fighters continued to whip up an atmosphere thick with fear and mistrust, the formidable new generation of Happy Valley memsahibs slept with guns under their pillows in fortified buildings to protect them from nocturnal attacks, while their husbands joined the Kenya Regiment and went off to fight the determined, fearless men hiding in the impenetrable forests of Mount Kenya and the Aberdares.

Long-haired and unwashed, the Kikuyu freedom fighters knew their way through the thickets and managed to sidestep danger in ways that flummoxed the British. Even RAF bombing of the mountain forests failed to dislodge them or sabotage their teams of supportive women who delivered food and messages. As Elspeth Huxley points out in Nine Faces of Kenya: ‘British soldiers in boots and smelling of soap and cigarettes had little chance of success against forest gangs in league with local fauna.’ Increasingly the Kenya Regiment was forced to rely on ‘pseudo gangs’ of white settlers, heavily disguised, venturing into the heart of the forest.

Times had to change and Jomo Kenyatta, Kikuyu leader of the Kenya African National Union (KANU) party, was released from detention in 1961 to become the country’s first Prime Minister when Kenya’s flag was raised at midnight on 12 December 1963 amidst jubilation and fireworks. It was time: India had shed British rule in 1947 and ten years later Ghana had become the first independent African British colony. As Jeremy Murray-Brown records in Kenyatta, the new Prime Minister (whose title was to become President the following year) said: ‘This is the greatest day in Kenya’s history and the happiest day of my life,’ smiling when the Duke of Edinburgh whispered: ‘Do you want to change your mind?’

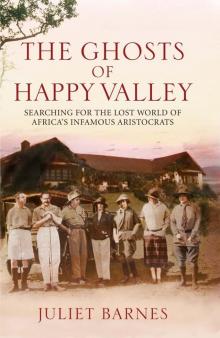

The Ghosts of Happy Valley

The Ghosts of Happy Valley